Historical Comments on the Baby Boom and Modern Fertility Rates

A response to what I'm sure what just a rhetorical prompt by Derek Thompson // The importance of casual historical analysis

Derek Thompson gave this prompt in his recent piece What Caused the 'Baby Boom’? What Would It Take to Have Another? (July 2025):

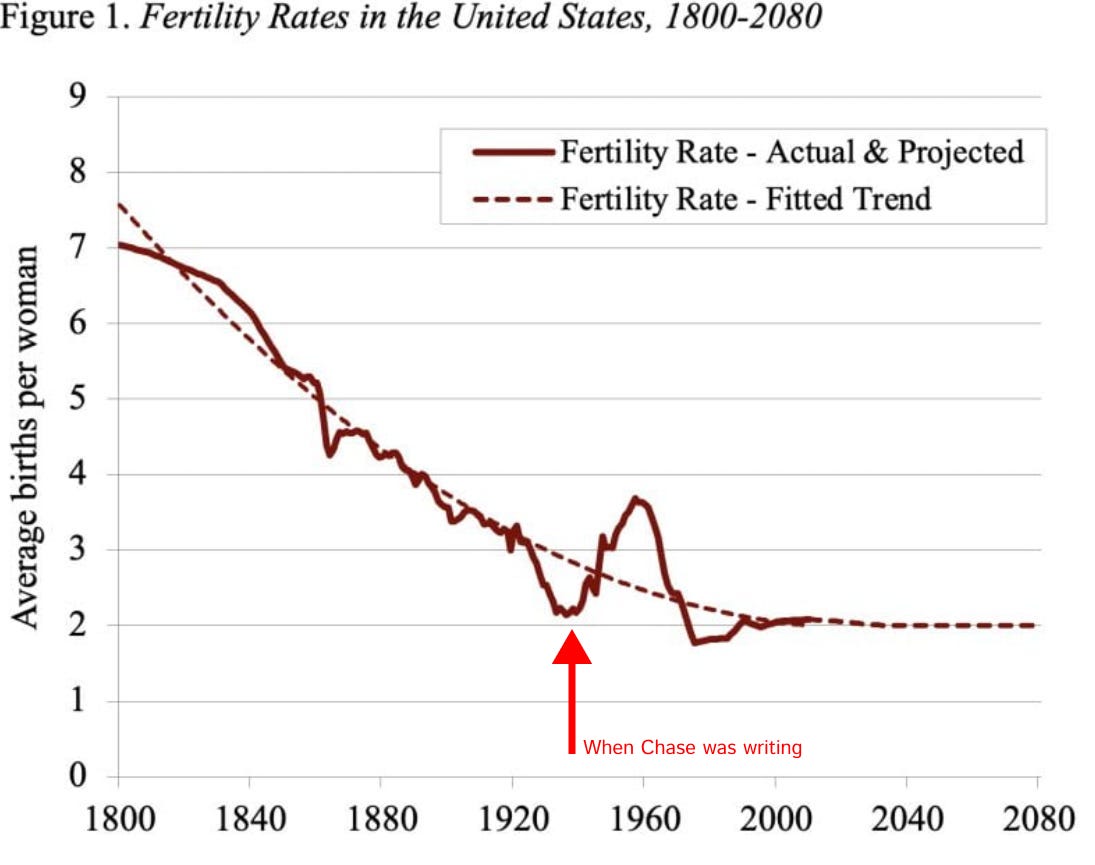

Imagine being a journalist or demographer in 1925. For the previous 100 years, going back to the early 1800s, the fertility rate in the U.S. and practically every other rich country had steadily declined toward the replacement rate of 2.1.

OK! Let’s take a look at what a famous contemporary writer1, Stuart Chase, said at the time. In the February 1939 edition of The Atlantic, Chase opens his piece “Population Goes Down” with a dramatic picture:

There are more than a million empty desks in the elementary schools of America this year. In 1930 the total enrollment was 21,300,000; in 1938 it had fallen to about 20,000,000…This is only the beginning.

Chase was writing at the contemporary low point of fertility in the United States. Below I’ve reproduced a graph that Derek used in his post, with a red arrow to emphasize what the world around Chase must have looked like.

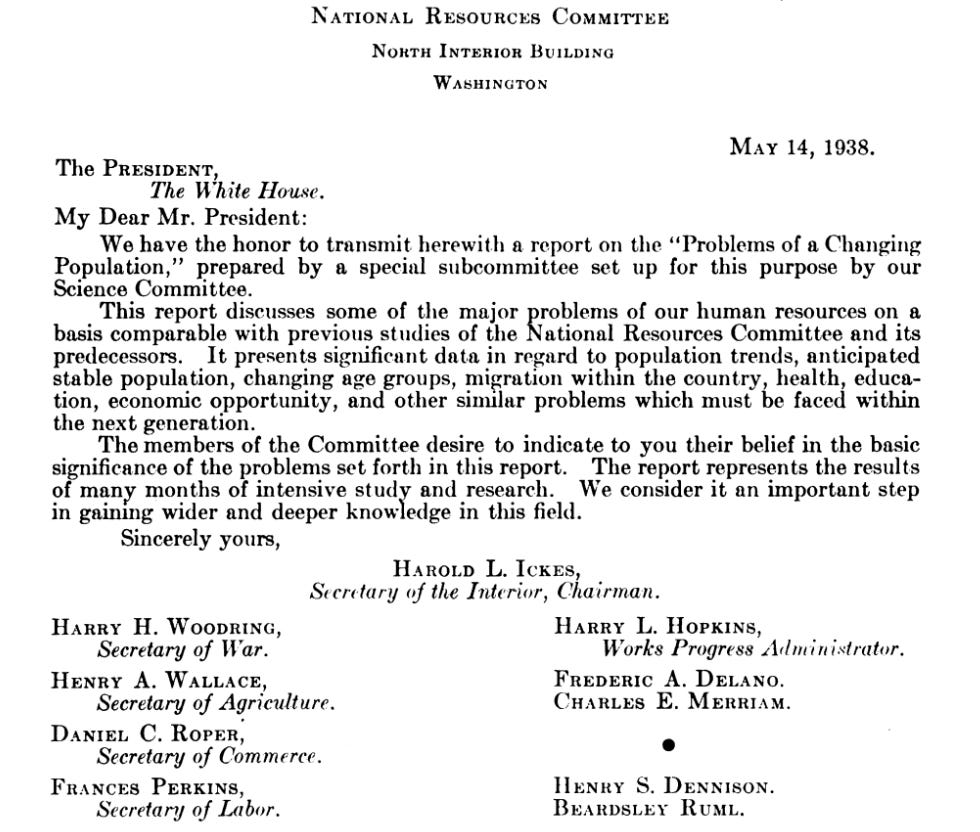

From his perspective, things were trending sharply and unambiguously. He had full confidence in the population projections released by the National Resources Committee in The Problems of a Changing Population (1938),2 which showed the U.S. population growing slowly before eventually plateauing and falling in the latter half of the twentieth century. Indeed, this report was made at the cabinet level to President Franklin Roosevelt, and exemplifies social policy thinking at the time:

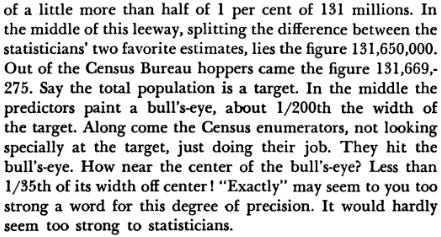

And when the results of the 1940 census were released not long after the report above, Chase was (epistemically) delighted to find that the U.S. population had landed directly between the two population estimates the authors of the 1938 report thought most likely: 131,308,000 and 131,993,000. In a 1941 pamphlet entitled “What the New Census Means,” Chase said:

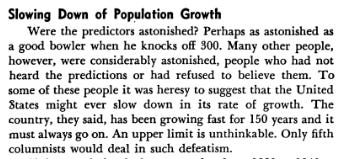

He then proceeded to take a victory lap:

Well, we know that pretty much right after all of this the U.S. entered the baby boom. Chase, standing in 1941, had been fully confident in future population projections showing slowing growth and eventual decline. He had the advanced statistics of the day on his side, and his underlying assumptions seemed reasonable enough. And yet he, and many others, got their predictions exactly backwards.

This doesn’t mean they were dumb, or even that their assumptions were unreasonable. I don’t want to paint them as simple. They were perfectly aware that their assumptions could be overturned by events, at the very least. For example, in his (May) 1941 pamphlet Chase says this:

One ought not even assume that Chase was pessimistic about our prospects of dealing with fertility and population decline (to say nothing of the changing ratio of young and old). Toward the beginning of his 1938 Atlantic piece he says, “…when an economic system built on three centuries of steady expansion encounters a population curve that is rapidly ceasing to expand, it is bound to buckle and crack—until adjusted to the new conditions.” And in the final paragraph he says, “One last prophecy…The reproductive index will move up again when children are wanted so badly that parents are at last ready to sink their prejudices and really safeguard the community against insecurity, unemployment, and war. Will the instinct for survival take care of this in due time? I think it will. It is a tough instinct.”

Finally, Chase was not sounding an emergency klaxon: “What is the [population curve] going to do to us here in America?…Fortunately, it moves slowly and nothing need happen very suddenly. If, however, we pretend it is not there and one day wake up, some unpleasant things might happen very dramatically…If we face the situation with our eyes open, we can probably handle it.”

Why look at what was said in the past?

The consonance of past and present is delightful and useful

A detailed look at the past helps you think about the present more clearly, and with less visceral attachment to the tribal thinking of the modern moment. History shares this context-switching advantage with good science fiction.

The more you look back to Stuart Chase’s confidence in the late 1930s and early 1940s, the more you think: “What might I be missing today? How can I see now what Chase and others did not see then? Is it possible? If it’s unclear, I must hold myself and others to a rigorous standard of thinking as we figure it out.”

Further: it is a simple human delight to see that people were not very different in the past than they are now, at least in some ways; that our failures and fortunes repeat; and that we can use this information to our advantage. For example, I’ve written elsewhere about New York’s housing supply crisis of the 1920s—it was almost a blow-by-blow repeat of the policy debate we’re having in our current shortage, and is useful in that very debate.3

Collateral discovery

You never know what you’ll find when exploring sources from the past, and collateral discoveries can prove useful to other interests—or hover in the back of your head, waiting for some future discovered connection.

For example: I frequently write about NYC’s education budget for Maximum New York. It is the largest part of our city budget by far, clocking in around $40 billion this year; NYC spends more per student than anywhere else in the country. These costs continue to increase even when pupil count decreases.

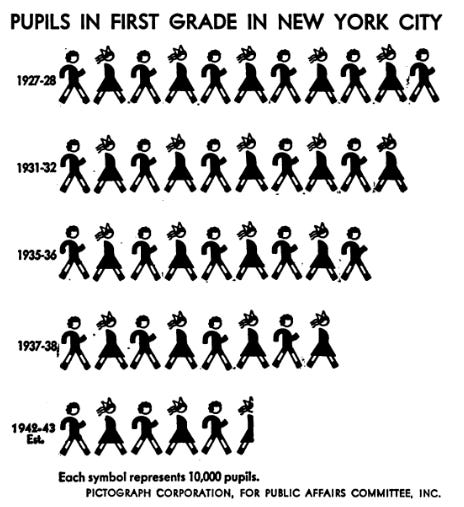

So imagine the researcher’s delight when I stumbled across this graphic and piece of information from Chase’s “What the New Census Means” pamphlet from 1941, which I originally read to flesh out his views on population rates (emphasis added):

New York City high schools in March, 1939, registered an all-time high of 257,498 students. By October, 1940, they had 3,000 fewer pupils. Elementary schools in New York lost 150,000 pupils between 1930 and 1940. Teaching staffs were cut down, saving the city $2,000,000. “The largest school system in the world,” said one of its officers sadly, “has now reached the contractive stage, and will from now on become smaller year by year. Plainly an epoch has been reached; one era has ended and another is to begin.” (this and graphic below can be found on pp.5-6)

As it turns out, I have gained a significant contemporary source to improve my writing about current NYC education budgets, and to help jumpstart some new historical research about city education budgets specifically. Clearly our education system used to function such that decreased enrollment led to decreased overall expense, which is the opposite of how it works now. And I never would have found this without exploring another topic more broadly.

It is good to build the muscle of constructing foreign contexts for analysis

People will say anything about what the past was like. But we can go check many of these claims. Some of them require looking up a document (“did this person really say that?”). Some require many documents (“what was the prevailing sentiment among academics at the time?”). Getting good at this, and cultivating instincts and taste in epistemic proxies based on these practices, will give you a better view of reality.

And then you realize: how you treat the past is how you treat the present. The present also requires this same kind of context-building, this same kind of evidence marshaling, this same kind of epistemic taste. It’s just easier to feel like you understand the present, because you live in it. But it requires work just like the past, especially if you’re deeply embedded in unhelpful information bubbles.

For example: now that you know about Stuart Chase, what do you think about this January 2025 report from McKinsey: “Dependency and depopulation? Confronting the consequences of a new demographic reality.”

So what else did that 1939 Atlantic article say?

I’ll end with some quotes from the article. It, as well as the other sources I list at the end of this post, could almost have been written today. Do with these what you will.

The state of the world

Only recently have statisticians refined their figures to the point of clear prediction. Their work is dramatic. They now realize that the zero hour is only a few years ahead. Presently not only will the growth rate disappear, but there will actually be fewer Americans on the continent. The repercussions are already considerable, and promise to be tremendous. Every business man, every government official, every banker, every school board, every citizen, will feel them.

The birth rate in America has been falling for a century. In 1875 it was 37 babies per thousand people per year. One thousand people means, roughly, two hundred families, and a new baby in every fifth family each year. In 1912, the rate was 26 babies, one a year in every eight families. In 1935 it was down to 17, and still falling. A similar trend is noticeable all over the world, especially in western countries. The Swedish rate is now down to 14, the English and French to 15. The German rate was 17 in 1930. It has increased slightly, under Hitler’s régime of forced parenthood, but experts think the gain will be temporary. Mussolini’s attempt to stimulate babies has had no appreciable effect.

On why the birth rate continues to fall (where have you heard this before…)

Why do they decline so universally and persistently? Here are some of the reasons.

It is now biologically possible to control conception. Birth-control methods are reaching every economic class in all civilized nations.

There seems to be an obscure biological factor which makes fertility lower in cities than in the country. Most of us are now living in cities or towns.

Young people marry later than they used to.

Many young people wish small families, or no families. Why do they not wish large families? For many reasons which are deep and complex. The World War had something to do with it. Widespread insecurity and unemployment frighten many prospective parents. Children in the handicraft age were an economic asset, helping around the farm; in the machine age, particularly in cities, children are an economic liability. Higher living standards have encouraged smaller families. A standard having been established, people are loath to slide down the scale.

A reproductive index of 1.0, or unity, indicates a stable population, where 1000 mothers produce enough girl babies to become 1000 mothers in their turn. If the index is above unity, there is a surplus of potential mothers and the population will expand. If the index is below unity, there is a shortage of girl babies and the population must fall. The Old Folks Home would have a reproductive index of zero.

Around 1930, the American index dropped below unity for the first time in history. It is now about .98. England is down to .74, Germany to .75, Sweden to .86, France to .93.

The effects of population decline on schools

A curious population wave is passing upward through the schools, with a heavy undertow of empty desks behind it. The wave was caused by the large number of children born immediately after the war. It is now roaring through the high schools. The undertow is caused by the sharply declining birth rates which set in around 1925. The undertow is just reaching the first years of high school. The United States Bureau of Education estimates a high-school peak enrollment of 6,135,000 in 1938-1939; then a recession as the wave rolls on to the colleges, and the undertow moves in. High schools are now stationary in New York, Ohio, Washington. Total publicschool enrollment in New York City dropped from 804,000 in 1930 to 753,000 in 1936 — 50,000 empty desks in one city. But effects of ‘the heavy losses in births between 1930 and 1937 are still to come.’

On children

Children consume 50 per cent more milk than adults. The milk industry is in for some painful readjustments.

As children become scarcer, they may be valued more highly, and spoiled more thoroughly.

As obstetricians decline, morticians will thrive. All industries catering to the aged will be stimulated.

Demands for more social security

When government budgets are relieved by a decline in school outlays, they will be simultaneously burdened by an increase in old-age pensions.

What we can be sure of is a sharp crescendo in demands for social security…

Political opinion may drift more to the conservative side — except in the matter of government pensions.

Realizing that housing demand (and prices) aren’t a function of population, but households!

This happens to be a drum I bang all the time (thank you for posting, Addison Del Mastro).

But, as an offset, houses may not follow the population curve. The number of families may increase long after the curve passes the crest. There will be fewer children, but more families.

Retooling an economic system, which made it much easier for past generations to succeed (goes Chase’s reasoning)

The outstanding economic problem of the next few decades will be to get an economic system geared for expansion, remodeled to operate in a community which grows slowly or not at all.

Business activity grew almost automatically in the past. More customers were at the counter every year. Thousands of citizens became rich simply by buying in at the 50 million population level and selling out at the 100 million level. You couldn’t lose. Those carefree days are over. There is not much increment in buying in at the 130 million level and selling out at 130 a generation later.

When the problem gets more visible, people will clamber

Many people want a return to the good old days of automatic expansion and little government interference. When they realize—say five years hence — that the Republican Party cannot give it to them, and that the population curve has much to do with it, we must brace ourselves for a terrific outburst of wild schemes to reverse the birth-rate trend. Congress will swarm with lobbies for taxes on bachelors, bonuses for twins, free trousseaus and curly-maple suites for brides, ‘Mrs. America’ cups for prolific ladies of all ages, penalties for the use of contraceptives, guaranteed jobs for bridegrooms. Pulpits will rock; editorial writers will let down their hair; statesmen will thunder about race suicide; generals will ask where our future defenders are to come from. The hullabaloo will be shattering — and the population curve will go serenely on its downward course. If Mussolini could not turn it, what chance has a democratic state?

The possibilities of immigration restriction (according to Chase)

Indeed, there is a definite bright side to this picture. With immigration greatly restricted in the future, the American people for the first time in history will have a breathing spell to become more integrated and homogeneous. There will be an end of ‘little Italys,’ ‘Wops,’ ‘Hunkies,’ ‘Yids,’ ‘Greasers,’ ‘ignorant foreigners.’ The melting pot will really melt. Household servants may become scarcer, which will cause their wages and status to rise. Educational standards can be lifted all around, as pressure on the schools relaxes. What we call ‘democracy’ can be brought nearer.

Two further notes from Chase’s 1941 pamphlet “What the New Census Means”

Eugenics is not feasible (although Chase notionally favors it)

Legislation cannot directly fix the fertility crash

Sources used:

“Population Going Down” in The Atlantic, by Stuart Chase (February 1939).

“The Problems of a Changing Population: Report of the Committee On Population Problems to the National Resources Committee” United States National Resources Committee. Science Committee (May, 1939).

“What the New Census Means” by Stuart Chase. Published in New York, New York, by Public Affairs Committee, Inc. (May, 1941). [Daniel’s note: this pamphlet repeats substantial material from Chase’s 1938 Atlantic article, although you’ll find plenty of new material at much greater length.]

“What Caused the 'Baby Boom’? What Would It Take to Have Another?” Derek Thompson (July 2025).

Further exploration:

Understanding the Baby Boom: The West has been below replacement fertility once before. Then came the Baby Boom. Understanding that boom may help us deal with today’s bust, Works in Progress (September 2023).

Dependency and depopulation? Confronting the consequences of a new demographic reality, McKinsey Global Institute (January 2025).

An understatement.

Said Chase in his 1939 Atlantic piece: “There is almost complete agreement as to the facts, and the shape of the American population curve in the years before us.” Further (bold emphasis added): “…the National Resources Committee at Washington released a report entitled The Problems of a Changing Population. Curves were plotted for a variety of assumptions. The report is undoubtedly the most authoritative and complete yet compiled. The authors favor two [population] curves as most probable.”

For examples, see: “A Renter’s Market, If You Can Keep It: How NYC’s Past Housing Booms Unlocked Tenant Power, Unit Quality, and Choice” (Maximum New York, July 2025).

“The Role of Market-Rate Rental Housing in New York City” (Maximum New York, January 2025).

This was super interesting! Thanks for sharing!