Lessons in History from Mercy Otis Warren

What can we pull from the introduction and chapter one of her 1805 book, "History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution"?

➡️ Skip to the beginning of the piece

Table of contents

Introduction: Mercy Otis Warren’s history (both biographic and vocational)

Post scriptum: John Adams’ angry response to Warren’s history

Introduction: Mercy Otis Warren’s history (both biographic and vocational)

Mercy Otis Warren (1728-1814) is one of the most important members of America’s founding generation that many people have not heard of. She published a contemporary history of the American Revolution in 1805, History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution, and was an active member of the Revolution’s social and political scene, corresponding and organizing widely from her and her husband’s home in Massachusetts.

Historian Lester Cohen praised her in this frank way: “In an era dominated by giants, she honorably may be numbered among the intellectuals of the second rank: those, for example, who served in colonial or state legislatures, the Continental Congress, and the Constitution-ratifying conventions and those who publicized the revolutionary cause through their writings.”1

A great defender of the American Experiment, she also penned a sharp Anti-Federalist pamphlet opposing the constitutional frame from the 1787 convention in Philadelphia (many of her concerns, like a lack of a bill of rights, would be remedied). The pamphlet was entitled, “Observations on the new constitution, and on the Federal and State conventions, by a Columbian patriot,” and was published in 1788. Notably, it carried the Latin subtitle “Sic transit Gloria Americana,” which is a play on the standard Latin “Sic transit gloria mundi,” which means “thus passes the glory of the world.” In Warren’s eyes, the new constitution threatened to undo the new nation.

One could say much about her influence, past and present, but for this post I’m going to present excerpts from the introduction and first chapter of her 1805 history. The point of this exercise is to show modern audiences a few things:

The people of the Revolutionary Era often thought similar things as us about their own time.

Many problems are a permanent part of the human condition, and you will find them replayed in every era. The past can be an excellent guide toward successful resolution, and a comfort in failure or difficulty.

The way you think about the past is likely the way you think about the present. If you are incurious about the past, and don’t seek to understand it and its people, you are probably badly botching your understanding of the present in the same way.

History is all about context. Past writers assumed common knowledge that…isn’t…today. For example, Warren assumed her audience had familiarity with British history, which is extremely relevant when explaining the American Founding (and beyond). Modern audiences, British and American, generally do not, and this will be readily apparent if they try to read her work. So they should ask themselves: what other references do I think I get, but are actually illuminated differently by contextual features I don’t appreciate? How would I know this? Per my point above, they could, and should, do this in the modern day with as much rigor.

The past is a foreign country, sure. It was extraordinarily different in ways the modern person would find hard to believe; when Mercy Otis Warren wrote, we still hadn’t invented regular timetables for oceanic freight, which would happen four years after her death in 1818. But the past would be shockingly familiar in other respects. Human nature endures. Ideas endure. Much of what would be labeled “modern thought” was very present hundreds of years ago.

People in the past write about their own time, just like we do. It wasn’t “history” to them yet. The idea that Americans were already writing histories of the Revolution by 1805 is surprising to some. But David Ramsay’s The History of the American Revolution came out in 1789!

I’m taking excerpts from her history’s introduction, entitled “An Address to the Inhabitants of the United States of America,” and the first chapter, “Introductory Observations,” because they lay out her general mode of thinking, and because they contain broad observations about the colonial period. It’s a good way to begin a historical inquiry—not by trying to ascertain the “correct answer” about an era, or mastering academia’s current consensus about it, but trying to put yourself in a contemporary head and just seeing what’s there. Questions and further thinking are natural from that point. In my view, the best professional historians, and the best non-historian people with the best historical perspectives, build pictures of past worlds this way.

All block quotes are from the 1989 reprinting of her history unless noted otherwise, and are followed by parenthetical page citations.

Opening thoughts on America and the new 19th century

The duty to the nation of those with talent, time, and means

Warren wrote her history to transmit her view of America’s founding principles to the present and future generation, so that they could live up to the promise of the new nation. For her, it was vital that readers understood both the events that occurred, and the character of those involved in those events. My readers should keep in mind that she wrote this over years, and finally published it when she was 77. It was, and is, a substantial achievement—and this was the kind of thing she thought proper to “improve the leisure Providence had lent.”2

At a period when every manly arm was occupied, and every trait of talent or activity engaged, either in the cabinet or the field, apprehensive, that amidst the sudden convulsions, crowded scenes, and rapid changes, that flowed in quick succession, many circumstances might escape the more busy and active members of society, I have been induced to improve the leisure Providence had lent, to record as they passed, in the following pages, the new and unexperienced events exhibited in a land previously blessed with peace, liberty, simplicity, and virtue. (xli)

I’m reminded of Theodore Roosevelt’s injunction to the higher classes of American society in his 1893 speech “The Duties of American Citizenship”:

It is just the same way with politics. It makes one feel half angry and half amused, and wholly contemptuous, to find men of high business or social standing in the community saying that they really have not got time to go to ward meetings, to organize political clubs, and to take a personal share in all the important details of practical politics.

In both cases, Warren and Roosevelt asserted a proper use of time for the wealthy and talented: service to the nation.

The assertion of women’s role in politics

Mercy Otis Warren was aware of her uncommon position as a woman active in Revolutionary politics. She was not alone, to be sure, but she was perhaps the most prominent, visible, and intellectually engaged, and she foregrounds that for her readers several times.

The solemnity that covered every countenance, when contemplating the sword uplifted, and the horrors of civil war rushing to habitations not inured to scenes of rapine and misery; even to the quiet cottage, where only concord and affection had reigned; stimulated to observation a mind that had not yielded to the assertion, that all political attentions lay out of the road of female life. (xli)

The present is evolving quickly with vast improvements, and more is expected in the future

One often sees commentary that laments the pace of modern change. And while our own era is certainly different from past iterations, this concern is not new at all. Mercy Otis Warren was definitely more of an optimist though—or rather, she did not write change off out of hand as an immediate problem.

Before this address to my countrymen is closed, I beg leave to observe, that as a new century has dawned upon us, the mind is naturally led to contemplate the great events that have run parallel with, and have just closed the last. From the revolutionary spirit of the times, the vast improvements in science, arts, and agriculture, the boldness of genius that marks the age, the investigation of new theories, and the changes in the political, civil, and religious characters of men, succeeding generations have reason to expect still more astonishing exhibitions in the next. (xliii)

The duty of Americans to unite under virtuous principle

Modern Americans might not realize just how foreign the original colonies were to each other. Founding Era calls for unity were existential, whereas today they have a squishier connotation. “On the eve of independence, residents of the thirteen colonies were more likely to be familiar with events and fashions back in England than they were with those of a neighboring colony.”3 When the first Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in 1774 to discuss how to respond to escalating British restrictions, John Adams remarked on the assemblage: “The Art and Address, of Ambassadors from a dozen belligerant Powers of Europe, nay of a Conclave of Cardinals at the Election of a Pope, or of the Princes in Germany at the Choice of an Emperor, would not exceed the Specimens We have seen.”4

In the mean time, Providence has clearly pointed out the duties of the present generation, particularly the paths which American ought to tread. The United States form a young republic, a confederacy which ought ever to be cemented by a union of interest and affection, under the influence of those principles which obtained their independence. (xliii-xliv)

The dangers of decadence and ease

Kids these days have forgotten the real history of the Founding Era, and don’t appreciate it

People forgot the revolution in many ways as soon as it was over, just like those who are barely 18 now have no real concept of 9/11 or whatever event the 30+ crowd wants to use as a benchmark.

Many who first stepped forth in vindication of the rights of human nature are forgotten, and the causes which involved the thirteen colonies in confusion and blood are scarcely known, amidst the rage of accumulation and the taste for expensive pleasures that have since prevailed. (4)

Decadent civilization, detached from feedback loops with rough reality, ruins societies

Warren was certainly not the first to worry about the corrupting effects of ease and decadence.

The Roman historian Sallust observed in The War With Catiline (emphasis added):

But when our country had grown great through toil and the practice of justice, when great kings had been vanquished in war, savage tribes and mighty peoples subdued by force of arms, when Carthage, the rival of Rome's sway, had perished root and branch, and all seas and lands were open, then Fortune began to grow cruel and to bring confusion into all our affairs. Those who had found it easy to bear hardship and dangers, anxiety and adversity, found leisure and wealth, desirable under other circumstances, a burden and a curse…Ambition drove many men to become false; to have one thought locked in the breast, another ready on the tongue; to value friendships and enmities not on their merits but by the standard of self-interest, and to show a good front rather than a good heart. At first these vices grew slowly, from time to time they were punished; finally, when the disease had spread like a deadly plague, the state was changed and a government second to none in equity and excellence became cruel and intolerable.5

And the Bible, particularly the Old Testament, is absolutely filled with warnings against the corrupting effects of ease. Here is Hosea 13:5-6: “I cared for you in the wilderness, in the land of burning heat. When I fed them, they were satisfied; when they were satisfied, they became proud; then they forgot me.”

Luxury, the companion of young acquired wealth, is usually the consequence of opposition to, or close connexion with, opulent commercial states. Thus the hurry of spirits, that ever attends the eager pursuit of fortune and a passion for splendid enjoyment, leads to forgetfulness; and thus the inhabitants of America cease to look back with due gratitude and respect on the fortitude and virtue of their ancestors, who, through difficulties almost insurmountable, planted them in a happy soil. (4-5)

A young Abraham Lincoln would warn of the dangerous temptations of ease to the United States in his 1838 Lyceum Address, “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions” (skip to the final bolded paragraph for the meat of the sentiment):

Through [the Revolutionary] period, it was felt by all, to be an undecided experiment; now, it is understood to be a successful one.--Then, all that sought celebrity and fame, and distinction, expected to find them in the success of that experiment. Their all was staked upon it:-- their destiny was inseparably linked with it. Their ambition aspired to display before an admiring world, a practical demonstration of the truth of a proposition, which had hitherto been considered, at best no better, than problematical; namely, the capability of a people to govern themselves. If they succeeded, they were to be immortalized; their names were to be transferred to counties and cities, and rivers and mountains; and to be revered and sung, and toasted through all time. If they failed, they were to be called knaves and fools, and fanatics for a fleeting hour; then to sink and be forgotten. They succeeded. The experiment is successful; and thousands have won their deathless names in making it so. But the game is caught; and I believe it is true, that with the catching, end the pleasures of the chase. This field of glory is harvested, and the crop is already appropriated. But new reapers will arise, and they, too, will seek a field. It is to deny, what the history of the world tells us is true, to suppose that men of ambition and talents will not continue to spring up amongst us. And, when they do, they will as naturally seek the gratification of their ruling passion, as others have so done before them. The question then, is, can that gratification be found in supporting and maintaining an edifice that has been erected by others? Most certainly it cannot. Many great and good men sufficiently qualified for any task they should undertake, may ever be found, whose ambition would inspire to nothing beyond a seat in Congress, a gubernatorial or a presidential chair; but such belong not to the family of the lion, or the tribe of the eagle. What! think you these places would satisfy an Alexander, a Caesar, or a Napoleon?--Never! Towering genius distains a beaten path. It seeks regions hitherto unexplored.--It sees no distinction in adding story to story, upon the monuments of fame, erected to the memory of others. It denies that it is glory enough to serve under any chief. It scorns to tread in the footsteps of any predecessor, however illustrious. It thirsts and burns for distinction; and, if possible, it will have it, whether at the expense of emancipating slaves, or enslaving freemen. Is it unreasonable then to expect, that some man possessed of the loftiest genius, coupled with ambition sufficient to push it to its utmost stretch, will at some time, spring up among us? And when such a one does, it will require the people to be united with each other, attached to the government and laws, and generally intelligent, to successfully frustrate his designs.

Distinction will be his paramount object, and although he would as willingly, perhaps more so, acquire it by doing good as harm; yet, that opportunity being past, and nothing left to be done in the way of building up, he would set boldly to the task of pulling down.

America was founded by British emigrants who were not corrupted by decadent ease, and who saw the rougher reality across the ocean as a refuge and opportunity

The love of domination and an uncontrolled lust of arbitrary power have prevailed among all nations, and perhaps in proportion to the degrees of civilization. They have been equally conspicuous in the decline of Roman virtue, and in the dark pages of British story. It was these principles that overturned that ancient republic. It was these principles that frequently involved England in civil feuds. It was the resistance to them that brought one of their monarchs to the block, and struck another from his throne.6 It was the prevalence of them that drove the first settlers of America from elegant habitations and affluent circumstances, to seek an asylum in the cold and uncultivated regions of the western world. Oppressed in Britain by despotic kings, and persecuted by prelatic fury, they fled to a distant country, where the desires of men were bounded by the wants to nature; where civilization had not created those artificial cravings which too frequently break over every moral and religious tie for their gratification. (5)

Thus a spirit of emigration adopted in the preceding reign [the Stuart monarchs] began to spread with great rapidity through the nation. Some gentlemen endowed with talents to defend their rights by the most cogent and resistless arguments were among the number who had taken the alarming resolution of seeking an asylum far from their natal soil, where they might enjoy the rights and privileges they claimed, and which they considered on the even of annihilation at home…Thus, through every successive reign of this line of the Stuarts, the colonies gained additional strength, by continual emigrations to the young American settlements. (5-7)

Religious intolerance and tolerance

Religious intolerance was widespread, and not confined to the puritans

Especially in the earliest days of settlement, the American colonies were natural homes to religious intolerance in some ways. After all, people left Europe because they had strong religious views—and many of those people belonged to the Church of England itself, especially in Virginia. They were not friendly to attempts to shape the colonies after different religious traditions.

Yet while we admire their [the first planters of the American colonies] persevering and self-denying virtues, we must acknowledge that the illiberality and weakness of some of their municipal regulations have cast a shade over the memory of men, whose errors arose more from the fashion of the times, and the dangers which threatened them from every side, than from any deficiency either in the head or the heart. But the treatment of the Quakers in the Massachusetts can never be justified either by the principles of policy or humanity…yet an indelible stain will be left on the names of those, who adjudged to imprisonment, confiscation and death, a sect made considerable only by opposition. (9)

The spirit of intolerance in the early stages of their settlements was not confined to the New England puritans, as they have in derision been styled. In Virginia, Maryland, and some other colonies, where the votaries of the church of England were the stronger party, the dissenters of every description were persecuted, with little less rigour than had been experienced by the Quakers from the Presbyterians of the Massachusetts. An act passed in the assembly of Virginia, in the early days of her legislation, making it penal “for any master of a vessel to bring a Quaker into the province.” (10)

You can see a similar history of religious intolerance in Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia (written 1781-2, publish 1787), which Warren would have read. From Query 17, on religion:

The first settlers in this country were emigrants from England, of the English church, just at a point of time when it was flushed with complete victory over the religious of all other persuasions. Possessed, as they became, of the powers of making, administering, and executing the laws, they shewed equal intolerance in this country with their Presbyterian brethren, who had emigrated to the northern government. The poor Quakers were flying from persecution in England. They cast their eyes on these new countries as asylums of civil and religious freedom; but they found them free only for the reigning sect. Several acts of the Virginia assembly of 1659, 1662, and 1693, had made it penal in parents to refuse to have their children baptized; had prohibited the unlawful assembling of Quakers; had made it penal for any master of a vessel to bring a Quaker into the state; had ordered those already here, and such as should come thereafter, to be imprisoned till they should abjure the country; provided a milder punishment for their first and second return, but death for their third; had inhibited all persons from suffering their meetings in or near their houses, entertaining them individually, or disposing of books which supported their tenets.

As time went on, and Americans approached their Revolution, religious toleration increased and became widespread—especially due to the waning influence of the Church of England (Anglicans)

In the following excerpt, she also notes that religious toleration coincides with the happy medium between barbarism and decadence (emphasis added).

The religious bigotry of the first planters, and the temporary ferments it had occasioned, subsided, and a spirit of candor and forbearance every where took place. They seemed, previous to the rupture with Britain, to have acquired that just and happy medium between the ferocity of a state of nature, and those high stages of civilization and refinement, that at once corrupt the heart and sap the foundations of happiness. (13-14)

Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia also affirms this trend toward toleration. From Query 17, on religion:

The Anglicans retained full possession of the country about a century. Other opinions began then to creep in, and the great care of the government to support their own church, having begotten an equal degree of indolence in its clergy, two-thirds of the people had become dissenters at the commencement of the present revolution. The laws indeed were still oppressive on them, but the spirit of the one party had subsided into moderation, and of the other had risen to a degree of determination which commanded respect.

Since no human can know everything, and we all think and perceive differently, we should be open to the idea that others have different parts of the truth that we do not

It is rational to believe that the benevolent Author of nature designed universal happiness as the basis of his works. Nor is it unphilosophical to suppose the difference in human sentiment, and the variety of opinions among mankind, may conduce to this end. They may be permitted, in order to improve the faculty of thinking, to draw out the powers of the mind, to exercise the principles of candor, and learn us to wait, in a becoming manner, the full disclosure of the system of divine government. Thus, probably, the variety int he formation of the human soul may appear to be such, as to have rendered it impossible for mankind to think exactly in the same channel. The contemplative and liberal minded man must, therefore, blush for the weakness of his own species, when he sees any of them endeavouring to circumscribe the limits of virtue and happiness within his own contracted sphere, too often darkened by superstition and bigotry. (11)

However, “tolerance” can go too far, and dissolve all good conviction

In this passage, Warren makes to great observations. The first is that she, and others, are ashamed of the conduct of their ancestors. They looked backward like we do today, shaking our heads—what a marvel moral progress is!

The second: she notes that extremist personalities often don’t moderate, they just move to another extreme. Here, she is talking about moving from dogmatic religion to militant atheism that sees no value in religion, and wants to directly tear it down with the same violence religions visited upon each other. The French Revolution did not help these worries.

The modern improvements in society, and the cultivation of reason, which has spread its benign influence over both the European and the American world, have nearly eradicated this persecuting spirit; and we look back, in both countries, mortified and ashamed of the illiberality of our ancestors. Yet such is the elasticity of the human mind, that when it has been long bent beyond a certain line of propriety, it frequently flies off to the opposite extreme. Thus there may be danger, that in the enthusiasm for toleration, indifference to all religion may take place. (12)

An (unintentionally) brutal description of Rhode Island and its people in the midst of the discussion on religious toleration

I don’t know whether Warren meant there to be any humor in this passage, but she was a talented playwright and satirist, so I wouldn’t be shocked. Regardless, it works well as understatement, to the detriment of New England’s smallest state.7

[William Penn] fixed his residence on the borders of the Delaware. He there reared, with astonishing rapidity, a flourishing, industrious colony, on the most benevolent principles. The equality of their condition, the mildness of their deportment, and the simplicity of their manners, encouraged the emigration of husbandmen, artizans and manufacturers from all parts of Europe. Thus was this colony soon raised to distinguished eminence, though under a proprietary government. But the sectaries that infested the more eastern territory were generally loose, idle and refractory, aiming to introduce confusion and licentiousness rather than the establishment of any regular society. Excluded from Boston, and banished the Massachusetts, they repaired to a neighboring colony, less tenacious in religious opinion, by which the growth of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was greatly facilitated. (10)

Closing Notes

Thoughts on Native Americans, their similarities to Europeans, and their understandable reactions to Europeans

While some modern eyes might turn away at a few phrases that Warren uses (like “savage”), they would err to do this. In doing so, they would miss the more profound points that she makes, and impute a worldview and manner that Warren did not possess. She saw the relationship between Native Americans and colonists in terms of their similarities, and in these similarities held up Native violence as understandable (even as she most certainly did not like it).

It is an undoubted truth, that both the rude savage and the polished citizen are equally tenacious of their pecuniary acquisitions…when the first rudiments of society have been established, the right of private property has been held sacred. For an attempt to invade the possessions each one denominates his own, whether it is made by the rude hand of the savage, or by the refinements of ancient or modern policy, little short of the blood of the aggressor has been thought a sufficient atonement. Thus, the purchase of their commodities, the furs of the forest, and the alienation of their lands for trivial considerations; the assumed superiority of the Europeans; their knowledge of arts and war, and perhaps their supercilious deportment towards the aborigines might awaken in them just fears of extermination. Nor is it strange that the natural principle of self-defence operated strongly in their minds, and urged them to hostilities that often reduced the young colonies to the utmost danger and distress. (13)

The straw that broke the camel’s back was not taxation without representation, but ingratitude on the part of the Mother Country toward her loyal colonies

“Taxation without representation” is the popular characterization of the American Revolution today, and it’s not wrong. But here Warren gets at something else: ingratitude. The American colonies had supported Britain in many ways, most recently (relative to the Revolution) by fighting and helping to finance the French and Indian War (1754-1763), which was the colonial theater of the related Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) between European powers.

Nor is it surprising, that loud complaints should be made when heavy exactions were laid on the subject, who had not, and whose local situation rendered it impracticable that he should have, an equal representation in parliament. What still heightened the resentment of the Americans, in the beginning of the great contest, was the reflection, that they had not only always supported their own internal government with limited expense to Great Britain; but while a friendly union existed, they had, on all occasions, exerted their utmost ability to comply with every constitutional requisition from the parent state. (16)

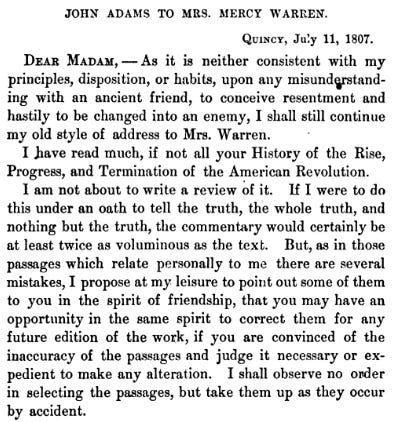

Post scriptum: John Adams’ angry response to Warren’s history

Warren’s history reviewed most of the Founders you’ve heard about, and that included her good friend John Adams—and the coverage was not always laudatory. After Adams sent her his first impressions of her book, the two went on to collectively exchange about 200 pages worth of letters (printed as below). In the end, after much effort and years, their friendship would be restored. But that’s a history for another time.

“Foreword,” History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution (1989), p.xvi.

Warren was assuredly familiar with Aristotle, but I’m not sure to what extent she shared the Aristotelian notion of “leisure,” which is that it was central to life, or to what extent she blended it with her undeniable work ethic. From Leisure: The Basis of Culture, by Josef Pieper: “The context of Aristotle’s words, and his other statement (in the Politics) to the effect that leisure is the center-point about which everything revolves [footnote: Politics, 8, 3 (1337b)], seems to indicate that he was saying something almost self-evident; and one can only suppose that the Greeks would not have understood our maxims about ‘work for work’s sake’ at all. On the other hand it must be evident that we no longer understand their conception of leisure simply and directly…it might be pointed out in reply that the Christian and Western conception of the contemplative life is closely linked to the Aristotelian notion of leisure. It is also to be observed that this is the source of the distinction between the artes liberales and the artes serviles, the liberal arts and servile work.” (p.21)

“John Adams to Abigail Adams, 29 September 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0109. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 1, December 1761 – May 1776, ed. Lyman H. Butterfield. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963, pp. 163–164.]

Although I will note, Adams continued to say directly: “—Yet the Congress all profess the same political Principles. They all profess to consider our Province as suffering in the common Cause, and indeed they seem to feel for Us, as if for themselves.” Clearly they were all there in a broad united purpose, but the fractious nature of the eventual continental government and Articles of Confederation revealed the depth of the colonies’ divisions as the war began in earnest in 1775-76.

Further, here is a consonant retrospective remark he made in 1809 about the 1787 constitutional convention, which he didn't participate in directly: “The convention I shall ever recollect with veneration. Among other things for bringing me acquainted with several characters that I knew little of before.”

From Sallust’s The War With Catiline, §10, Loeb Classical Library, (1921, revised 1931). The work was originally written around 40 BC.

Warren makes many passing references to the history of the British monarchy that would have been familiar to her readers at the time. The events themselves were also not that far in the past for her. Here she is referring to two Stuart kings: Charles I was overthrown and executed, and, after the restoration of the monarchy, his son James II was eventually forcibly replaced with William and Mary by parliament.

Personally, I think the history of the British monarchy is filled with useful, operationally relevant information. For example, this timely podcast on Henry VIII from Works in Progress.

If you’re curious, read about Roger Williams, who was exiled from Massachusetts for his (to them) heretical religious beliefs. He founded what would become Rhode Island in 1636, and there are several paintings about it (example 1, example 2). He was followed there by other Massachusetts exiles, including those resulting from the Antinomian Controversy (1363-38).

Always felt an affinity for her husband.