"Seeing" the World

Actually seeing what's right in front of you // the role of the arts in the academy

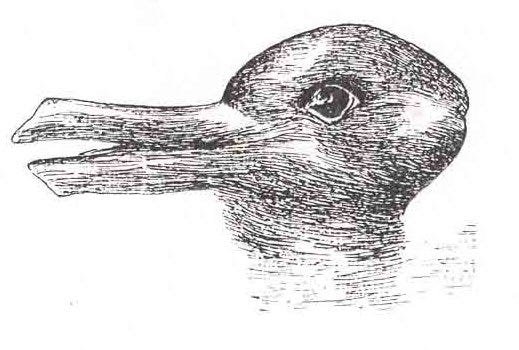

Everyone is familiar with optical illusions, where the nature of a visual presentation seems to “trick” the brain into seeing something else.

And when someone shows you an optical illusion, you’re primed to “find the trick.” Maybe you’ll succeed, maybe you won’t, but you’ll know there’s “something to see and perceive here.”

What many might not consider is that all of life, while not an illusion, is also always presenting us with a visual field that we can perceive better with more attention and skill. There’s no trick, but there is more to see.

Another way of thinking about this is when you haven’t seen something that was literally right in front of you. Everyone has done this at some point, and I did it literally yesterday. I was at a coffee shop in Brooklyn where I had never ordered a tea before, only coffee. Their overhead menu only had a broad “loose-leaf tea” item, but not all the specific teas they had available. I looked around the counter for some indication of what they had, but couldn’t find any, so I asked the barista, “What kinds of teas do you have?” With a pleasant smile, they pointed right in front of me, where I had been looking, to a lineup of glass jars with eight different options. My brain was primed to search for boxes, for signs, for letters, but not the particular kind of glass jar that was sitting right in front of me, each with neat labels indicating the kind of tea that was inside.

We will probably always ignore things that are right in front of us for lack of proper priming. Ideally you don’t do it too much, but it’s a human quality.

However, one can have one’s attention and focus trained to more deeply perceive and describe the visual field. Instead of explaining more about how to do this, I’m going to end this piece with two extended quotes that explain this phenomenon in the fields of fiction writing and drawing, although I’ve seen the same kind of explanation given in many fields. The more one sees practitioners in wildly different fields explain the same sort of “seeing” skill, the more fully one appreciates how fundamental a skill it is.

I’ll also note that training the skill to “see” properly belongs in a liberal arts academy. In a literal sense, one is more reality oriented when trained in this skill, and this improves communication, ability to conduct science, whatever you can think. The beautiful thing is that it’s often best trained through the arts.

From “Writing Short Stories” in Mystery and Manners (1969), a compilation of essays by Flannery O’Connor (pp. 92–93):

Fiction writers who are not concerned with these concrete details are guilty of what Henry James called “weak specification.” The eye will glide over their words while the attention goes to sleep. Ford Madox Ford taught that you couldn’t have a man appear long enough to sell a newspaper in a story unless you put him there with enough detail to make the reader see him.

I have a friend who is taking acting classes in New York from a Russian lady who is supposed to be very good at teaching actors. My friend wrote me that the first month they didn’t speak a line, they only learned to see. Now learning to see is the basis for learning all the arts except music. I know a good many fiction writers who paint, not because they’re any good at painting, but because it helps their writing. It forces them to look at things. Fiction writing is very seldom a matter of saying things; it is a matter of showing things.

However, to say that fiction proceeds by the use of detail does not mean the simple, mechanical piling-up of detail. Detail has to be controlled by some overall purpose, and every detail has to be put to work for you. Art is selective. What is there is essential and creates movement.

From Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Betty Edwards (1999 edition) (pp. 3–5):

(Note: if you think you “can’t draw,” I can’t recommend this book enough. You can.)

Drawing as a learnable, teachable skill

You will soon discover that drawing is a skill that can be learned by every normal person with average eyesight and average eye–hand coordination—with sufficient ability, for example, to thread a needle or catch a baseball. Contrary to popular opinion, manual skill is not a primary factor in drawing. If your handwriting is readable, or if you can print legibly, you have ample dexterity to draw well.

We need say no more here about hands, but about eyes we cannot say enough. Learning to draw is more than learning the skill itself; by studying this book you will learn how to see. That is, you will learn how to process visual information in the special way used by artists. That way is different from the way you usually process visual information and seems to require that you use your brain in a different way than you ordinarily use it.

You will be learning, therefore, something about how your brain handles visual information. Recent research has begun to throw new scientific light on that marvel of capability and complexity, the human brain. And one of the things we are learning is how the special properties of our brains enable us to draw pictures of our perceptions.

Drawing and seeing

The magical mystery of drawing ability seems to be, in part at least, an ability to make a shift in brain state to a different mode of seeing/perceiving. When you see in the special way in which experienced artists see, then you can draw. This is not to say that the drawings of great artists such as Leonardo da Vinci or Rembrandt are not still wondrous because we may know something about the cerebral process that went into their creation. Indeed, scientific research makes master drawings seem even more remarkable because they seem to cause a viewer to shift to the artist’s mode of perceiving. But the basic skill of drawing is also accessible to everyone who can learn to make the shift to the artist’s mode and see in the artist’s way.

The artist’s way of seeing: A twofold process

Drawing is not really very difficult. Seeing is the problem, or to be more specific, shifting to a particular way of seeing. You may not believe me at this moment. You may feel that you are seeing things just fine and that it’s the drawing that is hard. But the opposite is true, and the exercises in this book are designed to help you make the mental shift and gain a twofold advantage. First, to open access by conscious volition to the visual, perceptual mode of thinking in order to experience a focus in your awareness, and second, to see things in a different way. Both will enable you to draw well.

Many artists have spoken of seeing things differently while drawing and have often mentioned that drawing puts them into a somewhat altered state of awareness. In that different subjective state, artists speak of feeling transported, “at one with the work,” able to grasp relationships that they ordinarily cannot grasp. Awareness of the passage of time fades away and words recede from consciousness. Artists say that they feel alert and aware yet relaxed and free of anxiety, experiencing a pleasurable, almost mystical activation of the mind.

[…]

The key to learning to draw, therefore, is to set up conditions that cause you to make a mental shift to a different mode of information processing—the slightly altered state of consciousness—that enables you to see well. In this drawing mode, you will be able to draw your perceptions even though you may never have studied drawing. Once the drawing mode is familiar to you, you will be able to consciously control the mental shift.

Another good book on "seeing": Visual Intelligence by Amy E. Herman

In my liberal arts curriculum, students would learn to draw (to also help their observation skills), take music appreciation, and art history-- all of which will expand their ability to perceive the world around them, and relate to people and places in a great continuity.